On December 12, 1901, Guglielmo Marconi received the first, transatlantic, wireless message at Signal Hill in St. John’s, Newfoundland. It was an extraordinary accomplishment, one that ensured Newfoundland’s role in global communications would be heralded for many generations. But like everything associated with this island and its people, it’s the many periphery elements that make this story truly great.

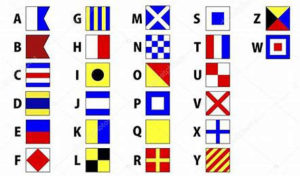

Despite the significance of this technological milestone, Signal Hill was named long before Marconi’s arrival. An honour that is appropriately attributed to a Signal House that announced the imminent arrival of ships that were hidden by the high hills surrounding the harbour’s entrance. Upon spying an approaching vessel, a signal man would raise a system of flags that notified the townspeople. Long before a ship reached shore; dock workers could organize berths, stevedores manned the stores, and shoppers anticipated the arrival of many exotic goods from around the world. Ironically, Marconi’s experiments meant we would no longer need a ‘Signal Hill’.

Of course, had wireless infrastructure been established before Marconi’s arrival, he would not have been granted permission to conduct these experiments in the first place. Many years before, Newfoundland had entered an agreement that assigned a monopoly on Trans Atlantic Communications to the American Telegraph Company when they successfully landed a cable that spanned the ocean between Valentia, Ireland and Hearts Content, Newfoundland (1866). A potentially caustic situation that was only recognized after the fact, at which time, they did indeed persuade Marconi to leave the colony. Doing so without hesitation. Knowing that radio waves could reach a network of transmission stations located throughout the mainland of North America, the island was never a part of his development plan anyway.

I love Marconi’s absolute conviction regarding his abilities and beliefs. For you must understand, these experiments defied the “science” of that time, causing respected colleagues like Alexander Bell to dismiss the attempt as “Madness”. The world had yet to discover, or even suspect the existence of an ionosphere, and therefore, “Radio waves can’t bend with the earth’s curvature. They will disappear into the vast empty space beyond the horizon.”

Any normal man would have likely abandoned the project when their receiving station at Cape Cod, MA was destroyed in a late season hurricane. Instead, Marconi loaded a haphazard compilation of equipment aboard a vessel that stormed its way through the rough, winter waters, steaming towards the remote, north eastern island of Newfoundland and its distinct advantage regarding proximity to England.

Poorly dressed in patent leather shoes and gloves, they fought gale force winds on Signal Hill, struggling to hoist temporary receiving antennae buoyed with weather balloons and kites, losing several before one finally clung, airborne long enough to receive three clicks in the Morse Code, the letter “S”

“S” for Success, or maybe Sell Phones, for this is certainly where the madness began.